The earliest donut shops were in ancient Greece and Rome

When it comes to the history of donuts and food, the delightful fried treats with a hole in the center boast a rich and sometimes tragic past that traces back to ancient Greece and Rome. On August 24th, A.D. 79, as Mount Vesuvius erupted, it’s unlikely that the ancient Romans, savoring sweet honey cakes (one of the early forms of donuts) at their local bakeries, realized these chewy delights might be their final meal. While we can’t determine how many residents of Pompeii were enjoying honey cakes that fateful day, we do know that cakes and breads were integral to their daily lives. The remains of ancient ovens, with their chimneys reaching towards the sky, along with frescoes depicting honey cakes, highlight the significance of baked goods in antiquity.

Yet, the ancient Romans were not the only ones indulging in honey cakes. The Greeks also enjoyed a type of yeasty bread known as Loukoumades, which can be seen as a variation of honey cakes. While modern athletes receive gold medals, ancient Greek Olympians were awarded Loukoumades, referred to as "honey tokens." Although the concept of restaurants as we know them today did not exist, certain social classes in ancient Greece embraced communal dining. Barley cakes were commonly served at these gatherings, often topped with honey and fruit, creating a primitive version of honey cakes or early donuts, if we stretch the definition a bit.

Donuts appeased both the gods of old and maritime sailors

In contrast to films like "Clash of the Titans," where the only offerings deemed worthy for gods and titans were innocent young maidens, the ancient world required far simpler tributes to satisfy its deities—just a few honey cakes would suffice. While it may have been an era when honey cakes were the equivalent of donuts, the Greek gods clearly expected food offerings from humanity to ensure Demeter's blessings for bountiful harvests and Dionysius's gifts of wine.

But appeasement didn’t stop there. When a fierce serpent, believed to protect Athens from invaders, rejected its share of honey cake, the Athenians were convinced that Athena herself had withdrawn the divine protection that could have thwarted the second Persian invasion led by Xerxes and his armada, which ravaged their coastline. In other regions of the ancient world, Ramses II of Egypt was so fond of honey cakes that they were depicted on the walls of his tomb.

It's still uncertain whether later sailors fared better than the Athenians or Egyptians with their food offerings. The whalers of the 19th century received a generous serving of donuts for every thousand barrels of whale oil they produced, although these treats leaned more towards the savory side. Cooked in whale oil, these donuts carried a distinctly fishy aroma, but it seems that these little morsels of fatty goodness were enough to keep the sailors motivated to continue their work.

A 600-year-old donut recipe survives from King Richard II's chef

If you were to explore "The Forme of Cury," a 600-year-old cookbook crafted by the chefs of King Richard II, you would discover an early recipe for donuts. Notably missing from this handwritten account are details such as oven temperatures, the inclusion of water as a crucial ingredient, and, for contemporary readers, a version of English that is easy to understand. However, what it lacks in clarity, it compensates for with fascination. "The Forme of Cury" was first published in the late 1700s, and for those who can decipher its text, the tales it shares illuminate the journey of foods as they transitioned from Arabic kitchens to Portuguese chefs and ultimately to the royal dining table.

The donut recipe itself suggests that at least one person at court might have been akin to a modern-day Dunkin' Donuts enthusiast. The king's passion for lavish feasts and celebrations, often costing tens of thousands of pounds, likely made indulging in donuts with Richard a delightful experience. The recipe begins with crushed almonds, combined with rice, and a touch of old-English enchantment to create an early version of donut holes. "The Forme of Cury," which translates to "A Method of Cooking" in contemporary English, is housed at the New York Public Library and holds the distinction of being the library's oldest English-language book in its collection.

Who brought donuts to the New World is contested

If you want to ignite a lively discussion among donut enthusiasts and food historians, simply inquire about who truly introduced donuts to the New World. The Dutch played a significant role in this culinary journey with their creation known as olykoek or oliebollen, which translates to "oily cakes" in English. These delightful, round morsels of fried dough, often filled with dried fruit and spices, first appeared in a Dutch cookbook in 1667. When the Dutch emigrated to America, they brought along their cherished recipes and passion for oily cakes, eventually arriving in New York City, then known as New Amsterdam. Among these early settlers was Anna Joralemon, who established the city's first donut shop in 1673.

Not to be outdone by their European counterparts, German immigrants in the U.S. clung to a tradition called "fastnachts." This custom required them to use up all their butter, sugar, and other delectable ingredients in the weeks leading up to Lent. In doing so, they created their own version of donuts to eliminate ingredients that might tempt them into sinful behavior during the fasting period. Thankfully for donut lovers, these fastnachts recipes made the journey across the ocean with the Germans. Unlike their Dutch counterparts, the German version of the treat did not include dried fruit. Instead, their fastnachts donuts were primarily made with milk, sugar, flour, and eggs, making them more akin to the donuts we enjoy today.

They weren't called donuts until the late 1700s

Not to be overshadowed by other competitors vying for the title of first name rights, Britain introduced its own interpretation of the donut into the proverbial arena. The British version of these sweet, fried bread delights claimed the name "donut." A recipe that called for "dough the size of a walnut," as noted in Michael Krondl's book "The Donut: History, Recipes, and Lore from Boston to Berlin," emerged in Britain around 1750.

If that narrative doesn't resonate with you as a fitting origin for the term "donut," there's another intriguing story in the history of food that might appeal to you more. According to donut lore, Hanson Gregory, a 19th-century sea captain, would take snacks on his voyages. These treats, crafted by his mother, Elizabeth Gregory, were deep-fried dough balls that contained walnuts or hazelnuts in the center. While this certainly enhanced the flavor, the primary reason for including nuts was to prevent the center of the treat from being doughy. Thus, dough filled with nuts evolved into what we now know as donuts.

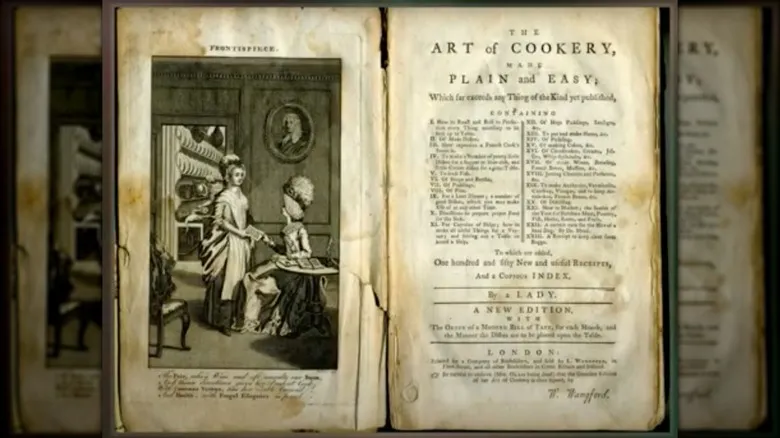

The first donut recipes in American cookbooks appeared in 1805

Although donuts have been popular in America since the late 1600s, they were not featured in any American cookbooks until the 1805 edition of Hannah Glass's "The Art of Cookery" was released. Earlier versions of the book existed, but this particular edition marked the first inclusion of American recipes. Throughout the 19th century, a total of 20 editions of the book were published, making it one of the most successful cookbooks of that time. While there is evidence that the term "doughnut" appeared in the language much earlier, some food historians argue that Glass's book represents the first documented use of the word. Despite the confusion surrounding this and the fact that Glass eventually declared bankruptcy despite her success as a cookbook author, her achievement remains significant. Similar to Noah Webster's American English dictionary, the first printed use of "donut" in Hannah Glass's book played a role in shaping the conversation about and appreciation for this beloved treat.

The origins of donuts are tied to Mardi Gras

Most people are familiar with the doll-filled king cakes of Mardi Gras, but fewer may realize that some delightful donut recipes also play a role in the celebration's sugar rush. Since medieval times, Europeans have cleared their pantries of rich ingredients like lard and sugar in preparation for Lent. Instead of discarding these items, they transformed them into donuts to be savored on Shrove or Fat Tuesday.

Various European nations have contributed their own unique Mardi Gras donut recipes. From Poland, we have the paczki, a donut that retains its center and is filled with fruit rather than air. The Portuguese introduced malasadas, triangular pieces of fried dough dusted with powdered sugar, which gained popularity in the US after a wave of Portuguese immigrants arrived in Hawaii in the 1800s. The French brought us beignets, while the Germans offered both fastnachts and Berliners, jelly-filled pastries that are quite similar to the Polish paczki.

Additionally, some innovative bakers across the country have taken the festive treats of Mardi Gras to the next level by combining donuts with king cake. Regardless of their form, it's hard to dispute that these sweet delights are a delicious way to use up pantry items before the season of Lent begins.

The first donut machine increased production and popularity

From an outsider's perspective, machine-made donuts may not seem as enticing as those crafted from scratch. However, the thought of producing hundreds in a single day makes the idea of a donut machine incredibly appealing. This was the challenge Adolph Levitt faced when soldiers, affectionately known as "doughboys," flocked to his shop upon returning home from Europe after World War I. These donut-loving veterans had developed a craving for the sweet treats after American Salvation Army Officers Helen Purviance and Margaret Sheldon delivered donuts to the trenches to boost troop morale.

Once back home, the doughboys sought out donut vendors like Levitt to provide them with one of the few comforts they had experienced during the war. Since the Harlem, New York, bakery owner wasn't particularly keen on shaping endless rings of dough by hand, he put his ingenuity to work and ultimately created a machine that produced the donuts. This machine dropped raw donuts into a vat of hot oil for frying, transforming Levitt's business. The success led him to establish the Doughnut Corporation of America, enabling other aspiring bakery and donut shop owners to purchase the machine for their own establishments.

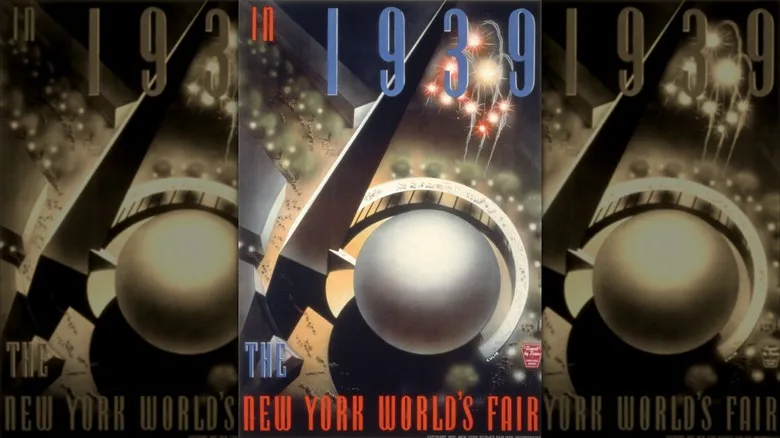

Donuts and coffee became a thing at the 1939 World's Fair

In a world where donuts seem to flow effortlessly from the coffee machines at Dunkin', it's difficult to envision a time when the pairing of these two delights symbolized the most innovative ideas for the future. However, back in 1939 at the New York World's Fair, coffee and its delightful companion, the donut, shone with the same allure as robots and View Masters. The organizers of the event promoted it as "The World of Tomorrow," and the Doughnut Corporation of America was present to add a sweet boost to the steps of visitors exploring the possibilities in the Food Zone.

At the previous World's Fair in 1933, food and agriculture exhibits were separated for the first time, marking a significant change in public perception of food production. The 1939 fair featured processed foods and beverages, such as Coca-Cola, Wonder Bread, and, naturally, donuts—products crafted by food scientists and processors rather than farmers—designed to satisfy the appetites of fair attendees. During this period, an advertisement for Mayflower Donuts and Maxwell House Coffee graced the cover of a menu for Mayflower Donuts shops. It embodied a sense of cheerful optimism that allowed people to momentarily overlook the recent hardships of the Great Depression and the looming threat of another world war.

Donuts came to stand for patriotism and progress

In the spheres of patriotism and advancement, it’s difficult to find a more dedicated food than the donut. Throughout both World Wars I and II, donuts served as a source of comfort for soldiers in the trenches and as a unifying element that fostered connections among people. A notable example is Irving Berlin's 1942 musical "This is the Army," which features a poignant song about lost love titled "I Left My Heart At The Stagedoor Canteen." In it, he wrote, "I kept her serving doughnuts till all she had were gone. I sat there dunking doughnuts till she caught on." After the war, John F. Kennedy delivered his iconic "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech, where, rather than simply expressing solidarity with the people of Berlin, he humorously referred to himself as a jelly donut. This misunderstanding arose from a media eager to simplify his message and overlook the deeper significance of his words during a tense period of the Cold War.

Simultaneously, societal progress, represented by the O-ring, continued to advance. The 1939 Expo certainly boosted the donut's potential to become the next big sensation, and with the Expo themed "The World of Tomorrow," it’s hard not to draw a link between donuts and progress. Additionally, many of today’s most cherished donut brands were founded during this era: Krispy Kreme in '37, and Winchell's and Dunkin' Donuts in '48, to name just a few.

Flavored donuts evolved in the 1960s

Maple bars. Chocolate donuts. Bavarian cream. The wide variety of popular donut types is hardly surprising to today’s donut enthusiasts. However, when Dunkin' Donuts launched its 52 flavors as part of its franchising strategy, it marked a significant shift in donut marketing and flavor innovation. Beyond the irresistible allure of sugar and fat that draws donut lovers to their nearest Dunkin' Donuts, the promise of a new donut flavor each week, all year round, was certainly a compelling incentive.

This weekly new flavor initiative began with the opening of Dunkin' Donuts' first franchise in 1955 in Dedham, Massachusetts. The concept stemmed from an earlier insight by the company’s founder, William Rosenberg, who in 1948 observed that the majority of sales from his food truck and later shop, Open Kettle, came from donuts and coffee. Eventually, Open Kettle transformed into Dunkin' Donuts, elevating customer expectations for donut shops with the introduction of exciting new flavors.

Donuts take off in Japan

Donuts are enjoying a moment in Japan. A visit to a Japanese donut shop rewards passionate donut enthusiasts with a wide array of ingredients to sample, each promising a uniquely Japanese flavor experience. Alternatively, they provide a comforting taste of home for those feeling homesick while exploring the Land of the Rising Sun. To grasp the appeal, it's helpful to examine some of the donut ingredients. The textured, round Japanese mochi donut is crafted from glutinous rice flour, while the Pon de Ring donuts from Mr. Donut are made with tapioca flour. This variety of ingredients lends each donut its own unique flavor and texture. However, Japan's donut scene isn't limited to Mr. Donut alone. American brands like Krispy Kreme and Dunkin', along with local favorites such as Miel Baked Donut, also contribute to the diverse selection available.

For those who are fans of Japanese culture, Mr. Donut, established in 1980, offers some extra attractions. A notable example is its collaboration with the Pokémon brand, which has introduced Pikachu-shaped donuts and other special items that Mr. Donut releases a few times each year.

Donut variations around the world

When a recipe travels across borders, it inevitably adapts to cultural tastes, ingredient availability, and the passage of time, and donuts are no exception. While Americans may favor glazed or cream-filled varieties, the preferences of donut enthusiasts in the U.S. don’t always align with those in other cultures.

In China, for example, donuts filled with pork and seaweed are quite popular. In various parts of Asia, people enjoy jalebi, which features ingredients like saffron, ghee, plain yogurt, and rose essence. In Indonesia, cheese-filled donuts add a unique twist for local fans. Meanwhile, churros have emerged from Spanish and Mexican traditions, and Bulgaria is known for its kanzanlak donuts. Each of these diverse donut styles serves as a testament to how the fundamental recipe for fried dough has evolved around the globe. Viewed from this perspective, it becomes clear how ancient honey cakes eventually transformed into the beloved donuts we know today.

Recommended

Give Pasta Fresh Seafood Flavor Using An Easy Canned Ingredient

Grocery Shop Like A New Yorker For Efficiency And Freshness

Trader Joe's Vs Aldi: Which Is Better For Vegan Grocery Shopping?

How Often Do Most Grocery Stores Restock Food?

Next up