Single malt

The phrase "single malt" is recognizable to many casual drinkers, even if they can't fully explain its meaning. Most people understand that it carries an air of prestige and exclusivity. We've been led to believe that single malt whiskeys are somehow more sophisticated than other varieties, and many assume it refers to a specific type of malt, which is a common misunderstanding. "Single refers to one distillery," explained Mark Tumarkin. Therefore, single malt whiskeys are those crafted solely from malt at a single distillery.

Traditionally, the term single malt has been linked to whiskeys from Scotland, where it is regulated, and any whiskey bearing that label must follow strict guidelines. For example, they must be distilled in pot stills—a slower and less efficient method than modern column stills, but one that retains more flavor. Additionally, the higher cost of malted barley compared to other grains used in whiskey production contributes to the premium price of single malt Scotch.

However, Tumarkin points out that producers in other countries have also embraced the label. "There are American single malts as well as those from Australia, New Zealand, France, and more," he noted. Yet, outside of Scotland, the term is not as clearly defined or regulated. "When it comes to American single malt or any other country, the rules are much more flexible," he said. "Not entirely, but it varies by country."

Age statement

When purchasing whiskey, you’ll frequently encounter an age statement, such as "10 years old." This number indicates the duration the whiskey has matured in a wooden barrel, a crucial process for enhancing its flavor. Since whiskeys are typically blends from various barrels, the age statement reflects the youngest whiskey in the blend. Therefore, a bottle labeled as 10 years old may also include whiskey that is 12 or 18 years old. It’s important to note that aging ceases once the whiskey is removed from the barrel; thus, a bottle of 10-year-old whiskey that has been stored in a closet for 50 years remains 10 years old.

However, similar to wine, older does not always equate to better. "Young whiskey can be vibrant, bold, and intense, while older whiskey tends to be more refined, subtle, and mellow," explains Mark Tumarkin. "Both have their merits." Generally, older whiskeys come with a higher price tag due to the extended time they occupy valuable space in the distillery. This cost has led producers (or their marketing teams) to promote older-age expressions as indicators of quality. While some well-aged whiskeys are exceptional, others may not be — it’s wise to consult product reviews before making a purchase.

You may also find many bottles that lack an age statement altogether. This absence doesn’t necessarily imply inferior quality. In fact, several reputable entry-level whiskey brands, like Jack Daniels, have garnered dedicated followings without age statements.

Blended whiskies

"Blended whiskey" is a term that may sound familiar to many casual drinkers, yet it is often misunderstood. The word "blended" refers not to the types of whiskey, but to the distilleries involved. A blended whiskey is created from whiskeys produced at multiple distilleries. Mark Tumarkin clarifies, "A blended malt is a malt whiskey made entirely from malted barley, but sourced from two or more different distilleries that have been combined." He cites Johnny Walker Green as an example of a blended malt whiskey. In this context, "blended" stands in contrast to "single," as in single malt.

The confusion arises because nearly all whiskeys are a combination of various batches, whether from the same distillery or different ones. Tumarkin notes, "Generally speaking, they're aiming for a consistent product. So they blend it together to achieve a specific flavor profile." Therefore, if you have a go-to whiskey that you enjoy repeatedly, you can thank the talented master blender who oversees the taste and maturation of all the distillery's barrels, skillfully finding the right mix to create the brand's signature flavor (which may vary each time). However, unless some of the whiskey is sourced from another distillery—a common and accepted practice—it is not technically classified as a blended whiskey.

Mash bill

In the process of whiskey production, the mash consists of a blend of crushed grains and water that are heated together to transform the starches in the grains into sugars. These sugars then ferment, forming the foundation of the whiskey. The term "mash bill," commonly found on whiskey labels and in reviews, refers to the specific grains used in the mash. This information is crucial for whiskey enthusiasts, particularly for those seeking a particular flavor profile or trying to avoid certain tastes, as each grain contributes its unique flavor and character to the final product.

Malted barley, which is barley that has been allowed to germinate and then dried to halt the process, is the primary — and often sole — grain used in Scotch whiskey. Mark Tumarkin remarked, "I believe barley is the best grain for whiskey production. It imparts caramel and bread-like notes. However, through fermentation and distillation, you can also achieve fruity flavors and a variety of other notes."

Corn, the main grain in bourbon, provides sweeter flavors compared to barley, which is why bourbon is typically sweeter. Rye, on the other hand, introduces bolder flavor profiles. Tumarkin noted, "Rye adds spicy and somewhat herbal notes, reminiscent of mint or root beer." Lastly, wheat contributes gentle, mild flavors.

Peat

Indeed, this is the same peat that enthusiasts of plants utilize to line their terrariums. It consists of compressed, partially decomposed plant material that creates thick layers across much of Scotland's landscape and other regions. Due to its abundance in Scotland, it has historically been extracted from the earth, dried, and used as a source of heat and cooking fuel, particularly in areas where timber was limited. This is where its connection to whiskey comes into play.

When malting barley for whiskey, maltmasters need to heat and dry the germinated barley to halt the germination process. Traditionally, in Scotland, the most readily available fuel for this task was peat. "However, it imparts a very smoky flavor, which adheres to the barley," explained Mark Tumarkin. "This flavor then carries through into the fermentation and distillation stages, resulting in peated, smoky whiskey."

With the advent of industrialization, many distilleries transitioned to coal, leading to the production of whiskeys devoid of the smoky essence. However, more remote areas, like Islay, have maintained the use of traditional peat and continue to craft highly sought-after peated whiskeys today. So, if you enjoy the robust, smoky flavor and aroma reminiscent of grilling, be sure to seek out a peated whiskey.

Rye whiskey

Rye whiskey is celebrated not only for its bold flavor but also for its rich history. When Scottish and Irish immigrants arrived in the United States, they brought their passion for whiskey and their distilling expertise. However, barley struggled to thrive in many of the regions where they settled. "Rye is a very resilient grass," Mark Tumarkin noted. "It can flourish in many areas where barley cannot. Consequently, in Pennsylvania and some neighboring states, farmers began cultivating rye."

With limited demand for rye, many of these immigrants turned to distillation to create a more lucrative and transportable product — thus, the first rye whiskey was created. Today, the rye whiskeys that contain the highest percentage of rye in their mash bills — and exhibit the most unique rye flavor — continue to be produced in Pennsylvania.

Rye whiskey even played a role in a military conflict. "Wars are costly, and George Washington and the government thought, 'How can we raise some funds? Let's impose some taxes. But what should we tax?'" Tumarkin explained. "Rye whiskey was a significant product in Pennsylvania and Maryland." This new whiskey tax was met with strong resistance from distillers, ultimately leading to the Whiskey Rebellion.

Tennessee whiskey

Although bourbon is closely linked to Kentucky, it is also produced in various regions across the U.S., including Tennessee, which has its own unique twist on this iconic spirit. "Tennessee whiskey is essentially bourbon," Mark Tumarkin noted. "However, there are two key distinctions: it must be produced in Tennessee, and it must undergo charcoal aging using maple charcoal, a method known as the Lincoln County process." If you're interested in sampling some, it's readily available. "The two major brands are Jack Daniels and George Dickel," Tumarkin mentioned. "Jack Daniels would like you to think this process is exclusive to them, but that's not accurate."

Tennessee whiskey, along with bourbon, emerged as a result of the Whiskey Rebellion. Following the successful quelling of the rebellion, George Washington provided incentives to persuade disgruntled Pennsylvania distillers to relocate to Kentucky. Once there, then-Governor Thomas Jefferson offered them free land in Bourbon County on the condition that they cultivate corn. They complied and subsequently began distilling whiskey from it, leading to the creation of bourbon.

"Bourbon must legally contain at least 51% corn," Tumarkin explained. It also has to be aged in new oak barrels. (He added that this is why many Scotch whiskies are aged in bourbon barrels; since bourbon producers cannot reuse them, they are happy to pass them along.) Additionally, almost all bourbons include some barley, which aids in fermentation, and rye or wheat often play significant roles in the mash bill.

Straight bourbon

"Straight bourbon" is a term you might encounter on labels when selecting a bottle. It signifies bourbon that not only fulfills all the legal criteria for the spirit (which includes a minimum of 51% corn, aging in new oak barrels, and an alcohol by volume of at least 40%) but also adheres to additional standards. The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, part of the Department of the Treasury, defines straight bourbon as whiskey that is "aged in charred new oak containers for a minimum of two years" and "may consist of blends of two or more straight bourbon whiskies, provided all are produced in the same state." Additionally, it cannot contain any added coloring.

What does this mean for you as a consumer? According to Mark Tumarkin, "It indicates good quality." However, he cautioned that the term "straight whiskey" does not guarantee the same level of quality. "It can be quite vague," he explained, noting that straight whiskeys may contain a low percentage of malt and higher amounts of neutral spirits, which are essentially vodka made from various ingredients. Consequently, he remarked, they are "usually not very good."

Bottled in bond

The phrase "bottled in bond" may sound somewhat legalistic, and that's because it is. However, when you spot it on a whiskey bottle, it serves as a solid assurance that the whiskey was crafted with honesty, free from unwanted additives, and with a transparent chain of custody throughout its production. "Essentially, it means that the whiskey is produced at a single distillery in a single year," Tumarkin explained. "It must be aged in new oak barrels, just like other bourbons, but for a minimum of four years." Most crucially, he noted, "It must be aged in a bonded warehouse." This requirement prevents any tampering with the barrels or their contents during the aging process.

Following the bottled in bond standards is optional, and currently, only bourbon makers pursue this designation. Tumarkin clarified that these standards originated as a consumer protection measure in the 1890s, when unscrupulous producers began diluting their whiskey with dubious substances. "Some of these additives were toxic, while others were merely molasses or food coloring. Some even included psychoactive poisons," he said. "[Bottled in bond] was essentially a way to guarantee quality at a time when producers were being quite reckless."

Cask strength

Legally, whiskey must have a minimum alcohol by volume (ABV) of 40%, or 80 proof, and consumers can find whiskeys available in various strengths. However, whiskey straight from the still is typically much stronger, as distillers dilute it with water to achieve lower proofs. Not all whiskeys are adjusted to these lower levels, though. If you encounter the terms "cask strength" or "barrel strength" on a label, it indicates that the whiskey is being offered at its original strength directly from the still, which can be quite potent, often exceeding 50% alcohol.

That said, this doesn't imply that it's merely a harsh alcohol experience with little else to offer. "While cask strength is generally higher in alcohol content, if you compare the same whiskey at lower and higher proofs, the cask strength version will be significantly more flavorful," explained Mark Tumarkin. "It may have a stronger alcohol presence, but it also delivers a richer flavor profile."

Tumarkin further noted that skilled distillers can create high-proof whiskeys that are smooth and less abrasive. "I have great admiration for those who can produce a higher-proof whiskey that is easier to drink than a lower-proof one," he remarked. Additionally, if you're uncertain about enjoying a cask strength whiskey, "you can always dilute it yourself" by adding a bit of water.

Scotch

Scotch is essentially whiskey produced in Scotland. This term encompasses a wide range of options, from popular mass-market brands like Johnny Walker to rare, artisanal single malts. The flavor profiles can vary significantly, ranging from light and refreshing cocktail mixers to rich, smoky varieties designed for leisurely sipping.

According to Scottish law, all Scotch must be distilled, aged, and bottled in Scotland, with a minimum aging period of three years in oak barrels. Unlike bourbon, Scotch does not have to be aged in new barrels; many distillers enhance their Scotch's unique flavors by aging it in barrels that previously held bourbon, sherry, or other spirits.

Tumarkin noted that Scotch varieties can also feature different mash bills. Malt whiskeys consist solely of malted grains, while grain whiskeys incorporate other grains like corn, wheat, or rye. Typically, grain whiskeys also include some malt. Given that whiskey-making has its roots in Scotland, true whiskey enthusiasts should take the time to learn about Scotch and its rich traditions.

Sour mash

The phrase "sour mash" might seem unappealing—who would want whiskey that tastes sour? However, it's important to note that this term doesn't describe the whiskey's flavor. Instead, it refers to the method of incorporating some leftover mash from a previous fermentation and distillation into a new batch of fresh mash. In fact, this practice of reusing old mash can actually help decrease the likelihood of sourness in the whiskey. "Typically, that leftover mash is fed to cattle, but if you take about a third of it and blend it into your next batch, it reduces the acidity," explained Mark Tumarkin.

It's worth mentioning that the sour mash process doesn't impart any unique flavors to the whiskey. While some producers highlight their use of sour mash (which is why you might see the term on labels), many others do not. "You'll find numerous whiskeys that don't promote this practice, yet they still use it," Tumarkin noted.

Recommended

Is A Coupe The Same As A Martini Glass?

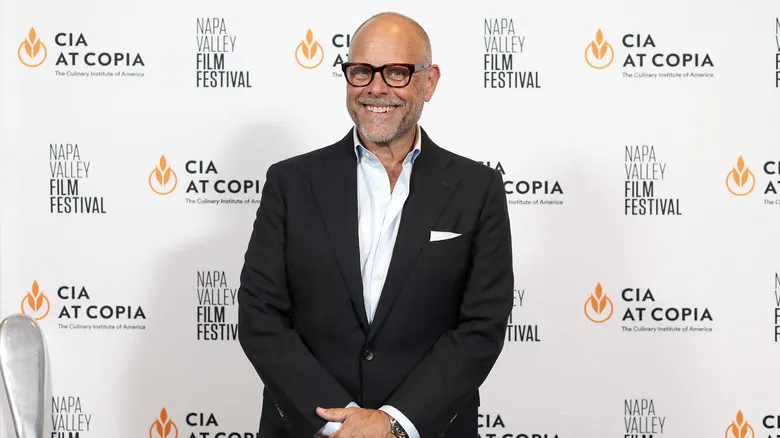

Alton Brown's Favorite Cocktail Combines 3 Strong Liquors

How To Make An Aperol Spritz - You're Doing It Wrong All Wrong

You'll Want To Sip Watermelon Paloma Cocktails Even After Summer's Over

Next up