Milkmen became a thing after people stopped keeping cows

The earliest documented instance of milk delivery in the United States took place in Vermont in 1785. Although significant urbanization surged during the 19th century, this initial milk delivery foreshadowed future developments. In an era when most individuals resided on small farms, obtaining milk and dairy products was straightforward. Typically, rural inhabitants kept one or two cows, which supplied them with the necessary milk and cheese.

However, as more people began to settle in urban areas throughout the 19th century, maintaining a personal cow for milking became impractical. Urban living spaces lacked the room for livestock, and modern refrigeration was not yet available. Additionally, caring for a cow was a time-consuming endeavor. As Sarah Wassberg Johnson noted, "Cattle must be milked twice a day while they are producing milk," and unpasteurized raw milk is "highly perishable."

This is where the milkman came into play, along with the iceman, who provided ice—an essential cooling solution of the time. Having a reliable delivery service for milk (and fresh ice) ensured that people received the dairy products they needed. It also alleviated the burden on farmers, who no longer had to discard milk that went unused by calves or their neighbors.

Animals were often involved in deliveries

The automobile was not created until 1886, when Carl Benz of Mercedes Benz applied for a patent for his gas-powered wagon, moving away from traditional horsepower. This means that a full 101 years elapsed between the first milk deliveries and the advent of the automobile. Nevertheless, milk delivery continued, relying on both human and animal power.

In the past, if milkmen weren't using their own strength—whether by bicycle or on foot—they typically relied on horses to pull their milk wagons. It was also possible to harness a couple of large dogs for the task. Many of these animals had remarkable and valuable abilities. As noted by Smithsonian Magazine in a 2012 article, "When yesterday's milkman walked between houses, his horse would quietly keep pace with him on the street."

Furthermore, the reliance on animals for milk delivery did not cease with the rise of automobiles. In fact, non-gasoline-powered options became particularly useful during World War II. Horse-drawn wagons filled the gap when gasoline rationing began in late 1942. Rubber for tires also became scarce for the same reasons as gasoline. However, since horses typically moved at a slower pace, the wear on the milk wagon's tires was not a concern. Additionally, the lack of gasoline posed no problem either.

Milk delivery is cow-to-table

Many contemporary milkmen source their milk from local dairies that ensure it reaches consumers within 48 hours of milking. This proximity to the beginning of the supply chain offers a significant advantage. Today, people are increasingly concerned about bacteria such as E. coli in the milk supply and the potential for dishonest food suppliers. Therefore, minimizing the number of stops between the cow and the table reduces the likelihood of these issues arising. Consumers are aware of the origins of their food, and suppliers are equally informed.

However, this level of transparency was not always present in the history of milk delivery. The safety of the milk supply became a pressing issue in the 1800s. According to Alex Prizgintas, President of the Woodbury Historical Society and owner of the Orange County Milk Bottle Museum, from the 1840s to the 1860s, swill milk—"a dreadful product from diseased cattle kept in filthy urban stables"—was responsible for numerous infant fatalities in New York City.

It took time for medical professionals to identify the source of the problem, which was traced back to urban dairies feeding cows leftover mash from distilleries. Ironically, this crisis led to the first shipment of fresh milk being transported by railroad to cities from regions like Orange County (where Prizgintas is based) in 1842.

Milk delivery and the milkman were big in Wawa's history

While Wawa convenience stores now offer a wide range of products, from sandwiches to fuel, they originally started as a dairy business at the turn of the 20th century. Founded in Pennsylvania, a region known for its significant milk production, it’s no surprise that milk was the cornerstone of Wawa's early success.

The dairy industry faced challenges in the mid- to late-1800s due to scandals involving poor-quality milk, which affected all dairy businesses, including Wawa. In response, the company took pride in providing high-quality milk, earning endorsements from many doctors. This "doctor certified" milk enhanced Wawa's reputation in the industry, as noted by the Times Herald.

Wawa established a robust milk delivery system, initially using horse-drawn carriages and later transitioning to motorized delivery trucks. The quality of Wawa's milk and dairy products, along with the dedicated delivery personnel, significantly contributed to the company's reputation and growth until the 1960s. Following that period, Wawa adapted its business model to compete with the rise of grocery stores, leading to the decline of the traditional milkman in its operations.

Bottles became necessary to keep the gunk out of the milk

Shiny glass milk bottles became emblematic of the traditional milkman. However, the initial efforts at milk delivery did not involve bottles at all. Instead, the milk delivery person transported large cans in their truck, with most carriers being men. Upon arriving at a destination, the homeowner would provide a jug or container for the milk to be poured into. This method of ladling fresh milk into individual containers raised the risk of contaminants, including animal hair and insects.

The introduction of the milk bottle in Brooklyn in 1878 by George Henry Lester transformed the role of the milkman for several reasons. As Alex Prizgintas notes, "[It] not only enabled milk to be transported in a hygienic manner but also empowered farmers economically by allowing them to sell milk directly to consumers."

Additionally, the milkmen who delivered jars on their regular routes also reaped the benefits of the milk bottle invention. Using glass bottles simplified the transportation of milk and allowed the milkman to keep a more precise record of how much milk each household received.

Milk boxes were built into houses

In some residences, the design of the house was influenced by the daily milk delivery. During the peak of the milk delivery period, many homes featured a milk box at the front, typically insulated and sometimes constructed from metal. Some of these compartments were even integrated into the home's design, allowing for milk delivery through a double-door mechanism. The milkman would place bottles of milk and other dairy items, such as butter, into the box through the exterior door. The homeowner could then access the delivery through the second door, which was located inside the house.

The milk box also functioned similarly to a mailbox. Families would leave their daily milk orders inside the box for the milkman. When it was time for billing, the milkman would include the bill with the milk delivery. The customer would then leave payment in the milk box for the milkman to collect on his next visit.

However, not all homes were equipped with milk boxes. To address this, some homeowners provided their milkmen with a house key, allowing them to enter the home and place the milk in the icebox if the homeowner was away. This system was a convenient arrangement based on mutual trust.

The milkman was as reliable as the postal service

There's a well-known saying about the postman delivering regardless of the weather. The same can be said for many milkmen, who often made their rounds every day of the week. (To be fair, some mail is now delivered on Sundays in the U.S., making it a seven-day-a-week service as well, though that wasn't always the case.) It's certainly not an overstatement to claim that milkmen walked as much as the average postal worker during their years of service, with some covering around 150,000 miles over a 50-year career, according to Wendover News.

In Europe, at least, milkmen were known for their unwavering commitment, delivering even in the face of wartime challenges that made it nearly impossible. As for why these milkmen were so courageous, Sarah Wassberg Johnson suggests it likely stemmed from "the perishable nature of milk and the fact that cows produce milk daily," making milk delivery essential no matter the circumstances.

World events greatly affected milk production and delivery

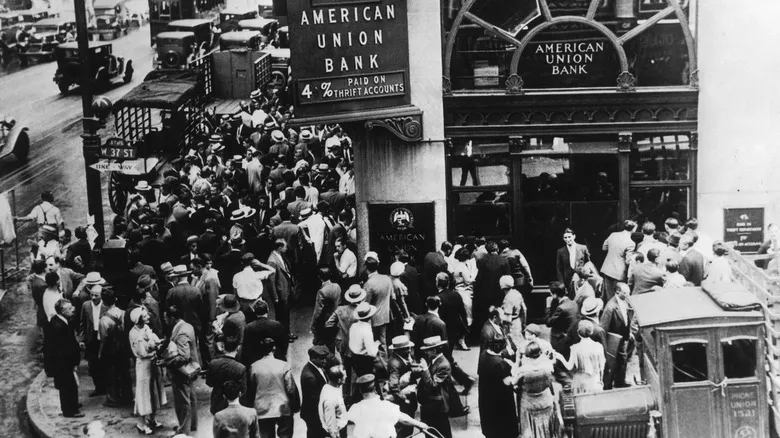

As anticipated, the Great Depression, along with World Wars I and II, had a profound effect on milk production and distribution. In the early 20th century, price gouging led to milk riots and economic struggles for dairy farmers in regions such as Wisconsin and New York. During World War I, grain prices in Europe surged, increasing production costs and further burdening dairy farmers. The situation for milk producers did not improve in the 1930s.

The significant drive to revive agriculture—and consequently, the dairy sector—emerged with the onset of World War II. Milk production was anything but sluggish during this period. The U.S. government requested dairy farmers to boost their output by 6% to 8%, according to Cumberland Times-News.

By 1942, the general public began to tighten their belts as wartime rationing limited their access to metals—particularly tin—and milk, both essential for the war effort to supply canned milk to soldiers abroad. Additionally, the two World Wars temporarily increased the number of female milk carriers on the streets. While women typically worked in creameries, they had not served as milk carriers until the wars necessitated the deployment of male carriers to the front lines.

Milk delivery could be a hard and dangerous job

Considering the cheerful depiction of milkmen in publications like the Saturday Evening Post, it’s not surprising that many people hold a sentimental view of the milk carriers of yesteryear. However, the reality was often quite different. For some milkmen, the job occasionally involved perilous situations, including attempts at highway robbery.

One milkman, Hiram "Ross" Graham, tragically lost his life to a gunman while making deliveries in Florida in 1968. Another veteran milk carrier, Carl Sorenson, recounted a robbery attempt he faced during his route in the 1970s.

The milk riots of the early 20th century also contributed to the violence faced by milk truck drivers. Dairy farmers in New York and Wisconsin initiated milk strikes in the early decades of the century to demand better prices for their product. They escalated these strikes by dumping milk, contaminating supplies with kerosene, and even using bayonets and tear gas to blockade milk deliveries. This environment made the job increasingly precarious and hazardous during that time.

Industrialization and health scares played big roles

A confluence of innovations and circumstances triggered the decline of the milkman. Following the end of World War II, rationing was lifted, and consumers were eager to purchase the goods—food, appliances, and conveniences—that wartime restrictions had forced them to forgo. With the widespread availability of refrigerators large enough to store everything bought at the supermarket, and the elimination of ration cards, people could stockpile as much milk as they desired.

Shoppers simply needed to head to the dairy section for milk and then explore other aisles for items like pasta and bread. There was no longer a need to wait for the milkman to deliver dairy products. It was akin to having access to the Black Market during the war, but in the post-war years, stockpiling was perfectly legal.

Moreover, pasteurization eliminated many harmful pathogens, such as tuberculosis, which meant that people no longer required daily milk deliveries, as pasteurized milk had a longer shelf life. This was complemented by the introduction of single-use cardboard milk cartons, which were less fragile than glass bottles and wouldn’t shatter if dropped.

Additionally, the surge in automobile ownership during this period allowed average Americans the freedom to visit supermarkets whenever they wished. This new age of mass production made milk consumption safer, more convenient, and more affordable without the need for a milkman.

Transportation advancements created less need for the milkman

Who among us hasn't found themselves stuck behind one of those massive 8,000-gallon trucks that resemble giant thermoses on wheels? Even the largest delivery vehicles used by traditional milkmen can't match the efficiency of this modern innovation in the dairy industry. The journey of milk in these thermos trucks starts at the dairy, where it is kept in enormous refrigerated containers. Before being transferred into the giant thermos, the milk undergoes antibiotic treatment and is tested for bacteria.

The drivers then transport the milk to processing plants, routinely checking its temperature and ensuring there are no traces of antibiotic residue along the way. Thanks to the impressive insulation of these trucks, the milk stays cold and fresh until it reaches the processing facility, where it is eventually packaged and prepared for market.

Once packaged, the milk is loaded back onto trucks, but these vehicles are significantly larger than anything a traditional milkman would operate. Ultimately, the truck makes its way to grocery stores, where the milk is unloaded in bulk onto the shelves. This method is far more efficient and cost-effective for delivering milk to consumers than relying on a fleet of old-fashioned milkmen.

The rise of grocery stores in the post-war era impacted milk delivery

Progress inevitably leads to some losses, and the milk industry, along with the traditional milkman, exemplifies this phenomenon. In the 21st century, many overlook this reality because obtaining a cold glass of milk is as easy as opening the fridge, pouring, and enjoying. When the milk runs low, a quick trip to the grocery store restocks the supply.

This convenience has fostered a kind of forgetfulness. As Sarah Wassberg Johnson notes, "The advent of commercial electric refrigeration, the introduction of coated cardboard cartons, homogenization, and the rise of automobiles significantly transformed milk production and distribution."

By the 1950s, over one-third of food was sourced from grocery stores. Roughly a decade later, that figure surged to 70%, according to Progressive Grocer. The pandemic further accelerated grocery delivery, which likely included a substantial amount of dairy, rising to 55%, as reported by the United States Department of Agriculture.

There’s a certain irony in this recent shift. Shortly after World War II, the cost of delivering milk, creamy cottage cheese, and other dairy products directly to homes became unsustainable. Many milkmen began to lose money on their routes due to the increased distances between stops, a result of suburban expansion, the rise of automobiles, and consumers opting to shop for themselves.

However, when the pandemic struck, economic factors once again brought delivery services to the forefront. COVID-19 restrictions confined people to their homes and limited most activities to essential workers, including grocery and delivery staff. Consequently, the milkman found himself back in business once more.

Recommended

The Real General Tso And How He Became The Namesake For Takeout Chicken

The Only Bread You'll Ever Need For A Perfect Bánh Mì Sandwich

Discontinued Canned Campbell's Soup We Wish Would Make A Comeback

Turn A Can Of Rotel Tomatoes Into Cheese Dip With Only 2 Ingredients

Next up