French and American politics played a role

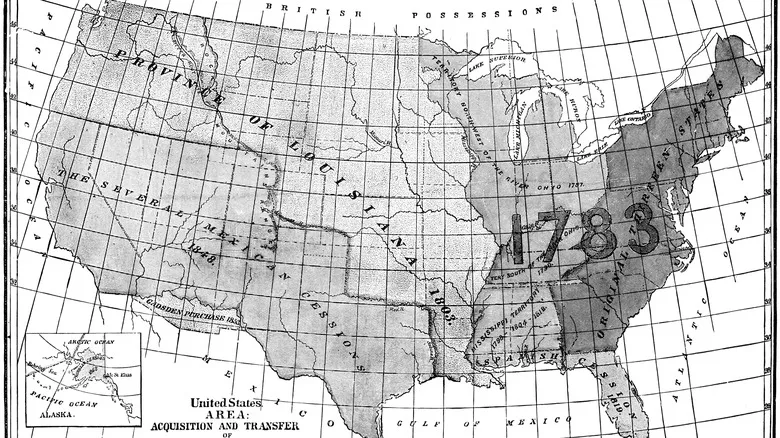

At the dawn of the 19th century, French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte envisioned grand ambitions for the Louisiana Territory, particularly New Orleans, as well as for other French colonies like Saint Domingue, now known as Haiti, which was renowned for its coffee and sugar production. During this period, Haiti was the leading producer and exporter of coffee globally, accounting for approximately 60% of the world's coffee sales, according to Sweet Maria's Coffee Library. In this context, one group of French colonies in the Caribbean was intended to supply goods, such as coffee, to another colony, Louisiana, especially the bustling port city of New Orleans. However, a significant obstacle arose in the form of the Haitian slave revolt, which lasted from 1791 to 1804, ultimately influencing the sale of the Louisiana Territory in 1803.

One might question why Napoleon opted to sell the Louisiana Territory to the United States, considering the profitability of Haitian crops. Essentially, for the arrangement to be viable, Haiti's coffee, sugar, and other exports needed to be included. However, following the revolt, these imports came to a halt, and with the loss of Haiti, the Louisiana Territory, including New Orleans, lost much of its appeal for Napoleon. The sale resulted in vast expanses of land, a valuable seaport, and a number of French settlers, all of which laid the groundwork for New Orleans to emerge as one of the world's leading coffee cities. This also paved the way for chicory to gain a strong foothold in the city when the circumstances aligned.

Mixing chicory with coffee started during the Napoleonic Wars

In 1806, Napoleon imposed an embargo on British trade, prohibiting any imports from Great Britain into French ports. Consequently, coffee imports across Europe plummeted, prompting coffee enthusiasts throughout the continent to seek a suitable alternative. This is when chicory emerged as a popular substitute for coffee among Europeans and became an export product that the emperor could send to the New World in the early 19th century.

However, not everyone was pleased with chicory. President Andrew Jackson believed that the chicory-based coffee alternative produced a subpar beverage. He dedicated considerable effort to persuading the public to choose coffee over chicory, or at least to consider a blend of the two. By 1812, Napoleon's vision of a Europe unbound by the morning ritual of caffeine consumption had faltered. Nevertheless, there was a silver lining: by this time, chicory had firmly established itself as coffee's counterpart and complementary ingredient in the eyes of the French, both in Europe and in America—a useful substitute when the cannons of the Civil War began to roar.

An enslaved woman founded coffee culture in New Orleans

Famous coffee establishments that offer chicory coffee, such as Cafe Du Monde, likely wouldn't be what they are today without the significant contributions of a formerly enslaved woman named Rose Nicaud, also known as Old Rose. Living in the early 1800s, she is recognized for launching the first coffee stand in the city, thereby laying the groundwork for coffee culture in New Orleans.

Originally from Haiti, Rose Nicaud's circumstances in America allowed her a degree of mobility, thanks to a contract she negotiated with her enslaver. This arrangement enabled her to set up a weekend coffee stand in the French Market, where she sold her unique blend of chicory coffee, located near where Cafe Du Monde would eventually open about 60 years later. The French Market was also close to St. Louis Catholic Church, providing Rose with a steady stream of customers eager to purchase her coffee after mass.

It has been reported that during her peak, she earned the equivalent of $1,400 to $1,600 a day in today’s currency, according to The Iron Lattice. Ultimately, Rose Nicaud was able to secure her freedom and that of her husband by leveraging the manumission laws in Louisiana. As a fitting conclusion to her story, it’s noteworthy that centuries later, she inspired a coffee shop named in her honor: Cafe Rose Nicaud.

Wartime blockades caused coffee to become scarce in New Orleans

In the city of New Orleans, any agricultural produce was primarily brought in by boat from the harbor. Before the Civil War, commerce served as the rich foundation that nurtured life in and around the Big Easy. However, a Union blockade of the Port of New Orleans nearly halted all trade, including the coffee imports arriving from the Caribbean, the Americas, and Cuba. With no harbor access for the vessels transporting coffee and other goods, the Big Easy (and beyond) faced a significant shortage of caffeinated beverages during the war.

To cope, New Orleans residents sought to stretch their existing coffee supply. For those of French descent, chicory emerged as the clear choice. They had learned that roasted chicory root offered a flavor and texture reminiscent of coffee. Moreover, as Kayla Stavridis notes, "Chicory contributes a unique taste — slightly earthy, nutty, and sometimes described as a bit 'woody' — that is distinctive to NOLA's blend."

Rather than diminishing the coffee experience, the combination of coffee and chicory enhanced its flavor, unlike many other wartime substitutes. Consequently, New Orleans residents didn’t feel deprived of coffee when enjoying this blend. Additionally, chicory could be cultivated locally, which helped the city's inhabitants remain less susceptible to the disruptions of war and the challenges it posed to the coffee supply chain.

Cafe Du Monde was established during the war

Every day, at every hour, without fail (except for Christmas), Café Du Monde in New Orleans serves up two signature items: a generous portion of square-shaped French donuts known as beignets and steaming cups of café au lait, made from a blend of coffee and chicory root. Established over 160 years ago, this iconic café has been offering its coffee-chicory mix for most of its existence.

The fame of this New Orleans establishment goes beyond being the oldest in the city. It was founded in 1862, during the second year of the Civil War, and has withstood the trials of war and the numerous hurricanes that have battered the city over the past century and a half.

While contemporary coffee culture in New Orleans sometimes caters to those who enjoy flavored drinks reminiscent of chocolate bars, Café Du Monde remains steadfast in its tradition. It’s the go-to spot for a classic café au lait, the same kind that would have been enjoyed during the Civil War—an equal blend of coffee and chicory, with just a splash of milk to give it a warm, golden hue.

Soldiers suffered due to the lack of coffee

The Union blockade of the Port of New Orleans had an immediate impact on residents of the city, but its repercussions extended far beyond its borders. Troops on both sides of the conflict experienced shortages of coffee due to the blockade. However, the North found some relief when President Lincoln discovered a new source of coffee in Liberia, allowing shipments through other American ports outside of Louisiana.

In contrast, the South, including Confederate soldiers, faced a much harsher reality. Initially, Southern soldiers received their coffee rations, but by 1863, supplies had dwindled to nothing. As noted by the American Battlefield Trust, one soldier candidly expressed the dire coffee situation in his journal, stating, "We are reduced to quarter rations and no coffee. And nobody can soldier without coffee."

The circumstances became so dire that soldiers resorted to extreme measures to obtain coffee. Much like the residents of New Orleans, they improvised by stretching their limited coffee rations with various substitutes, such as okra seeds, cornmeal, cottonseed, rye, parched wheat, sweet potatoes, and, of course, chicory. Yet, even mixing coffee with chicory proved insufficient for some. Certain Confederate soldiers began searching through abandoned Union campsites in hopes of finding any leftover coffee beans.

New Orleans still plays a critical role in modern coffee culture

"New Orleans boasts a coffee culture that is truly unique," states Kayla Stavridis. The sheer volume of coffee that flows through this vibrant city certainly supports this claim. In the past decade, it has not been uncommon for New Orleans to receive around 250,000 tons of coffee in a single year—enough beans to brew 20 billion cups of coffee.

Yet, the city's coffee culture remains deeply connected to its origins. The tradition of the mid-morning coffee break, where individuals pause their workday to enjoy coffee and catch up with friends, began in the Big Easy during the 1920s. Stavridis highlights the essence that laid the groundwork for this practice in New Orleans: "Coffee shops in NOLA embody community, hospitality, and a leisurely pace—sipping a cup of café au lait (often crafted with the renowned chicory blend) at a local café is more than just a caffeine boost; it’s woven into the city’s social fabric."

Vietnamese coffee, known for its robust flavors and French influences, has also established a presence here, thanks to immigrants who have opened Vietnamese coffee shops throughout the city. Many of these establishments pay tribute to their new home by blending their already-strong coffee with chicory, a hallmark of NOLA's coffee scene. This fusion seems almost inevitable, considering the history of chicory as a coffee substitute in the Big Easy. As Christopher Falvey notes, "People in New Orleans have a penchant for bold flavors. [...] When it comes to coffee, we prefer it very, very strong. Chicory enhances that."

Recommended

Why Dipping Your Cinnamon Rolls In Chili Just Works

The Important History Of Soul Food In Southern America

Colorado's Pueblo Slopper Is The Regional Dish That Tastes Better Than It Sounds

How Did Turkey Become The Default Main Course For Thanksgiving Dinner?

Next up